Religion with a lower-case r

A great remedy for the meaning crisis that few people seem to want.

1.

It is no longer novel to remark that Americans are undergoing a crisis of meaning. The basic theory, best articulated by cognitive scientist John Vervaeke, is now widely known: that for centuries, people in the West had a series of organizing principles, communities, and structures that gave meaning to their lives — religion, shared cultural values, meaningful work, expectations for family life — but these institutions have eroded, leaving people with a loss of meaning, purpose, and vitality. That, in turn, have led to a constellation of other crises: increases in deaths of despair, losses in community coherence, an embrace of reactionary ideologies, including nationalism and anti-feminism.

The causes of the crisis are many, including challenges to religion from science, the ‘Sixties’ rejection of traditional values, social justice movements (feminism, LGBTQ, BLM, MeToo) upsetting traditional hierarchies and gender roles, and, most recently, information technology, which has made us lonelier and angrier. And the fruits are everywhere: the masculinity crisis has led to online nihilists shooting up schools, influencers capitalizing on white male rage, and the spiral of toxicity well-dramatized in the recent Netflix series Adolescence. Many men pine for some fictive, Bronze Age arcadia when the rules were clear for everyone, and men were on top.

There is much more that has been said about the meaning crisis — I recommend Vervaeke directly and one of his frequent collaborators

. Here, I’m interested in what to do about it.2.

A funny thing about the meaning crisis is that liberal-minded people talk about it a lot, but so far, only conservative antidotes have really caught on: religion, nationalism, and in the case of young men, a re-affirmation (often with a middle finger raised) of pre-feminist ideals of masculinity.

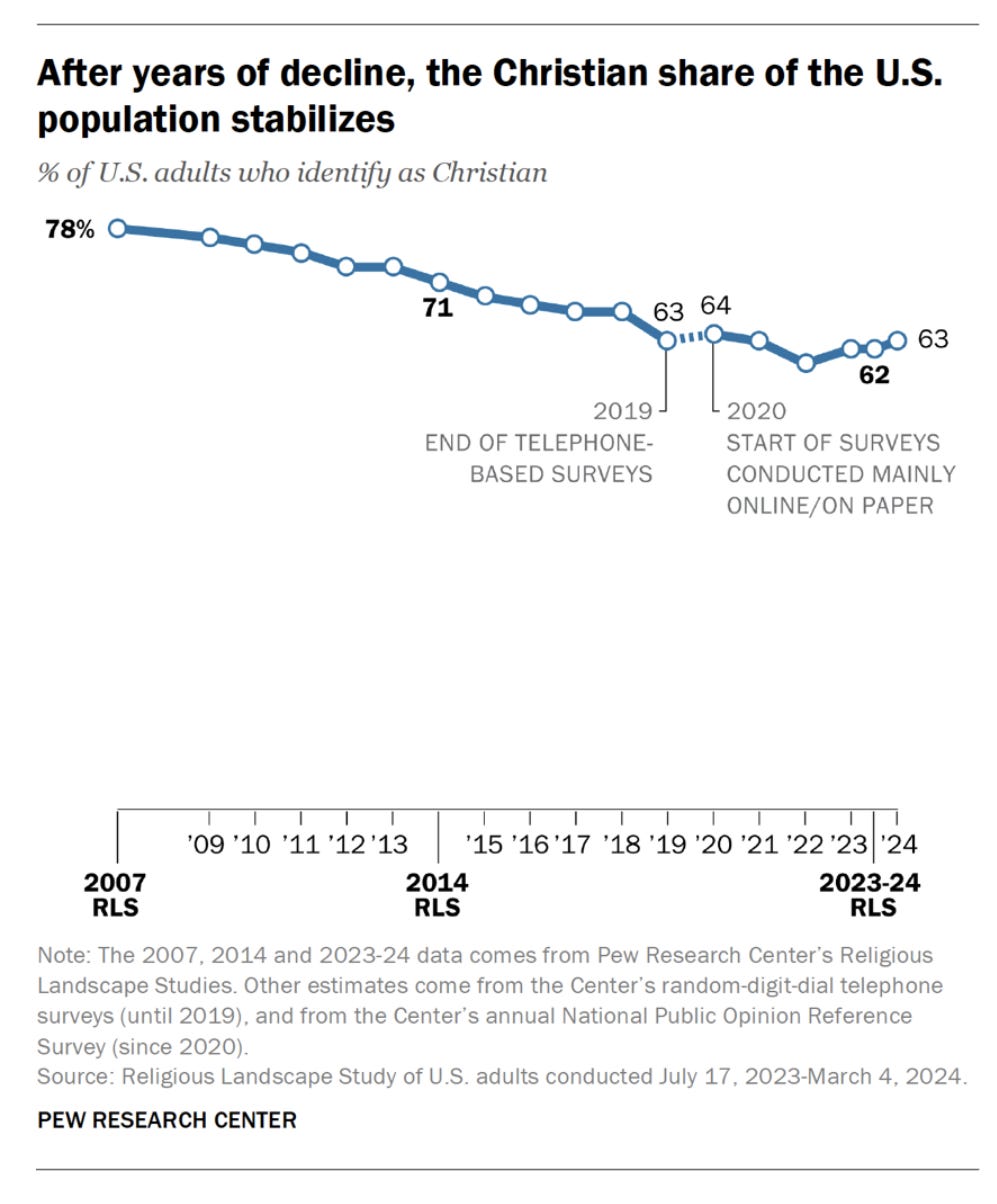

In terms of religion, statistically, young people remain less religious than older ones: in the 2024 Pew Religious Landscape Study, 54% of 18- to 29-year-olds identified with a religious tradition, compared with a 65% of 30-49, 77% of 50-64, and 83% of those 65 and over. However, the overall decline in Christian self-identification has stopped, and the cultural prevalence of Christian influencers has increased. Figures like Joe Rogan, Jordan Peterson, the late Charlie Kirk, and newly-mainstreamed neo-Nazi Nick Fuentes have said loudly that we need religion to provide meaning, and people seem to be listening. JD Vance’s conversion story, which I’ve written about before, tells a similar tale. Joe Rogan, who may still be the most influential media figure in America, said last year that “we need Jesus” as a foundation for morality.

And in terms of nationalism, the resurgence of ‘thick’ nationalisms across the Western world is now the defining political trend of the decade. Nationalisms respond to many things: migration and demographic change, the loss of economic opportunities in the face of globalization, resentment over changing social hierarchies — but also the yearning for a time of coherence, meaning, and community in the face of these and other changes.

Now, as with all nationalisms (and fascisms, if you prefer that word), appearance is more important than reality. The Trump aesthetic — the hair and makeup, the cheap gold leaf, the ostentatiously altered female subordinates — is an apt reflection of the priority of appearance over reality. Obviously, Trump’s economic policies hurt working people. But his rhetoric, bluster, and taboo-shattering boldness promise (impossibly) a return to the old ways and affirmation of communal identity. We are not meant to pay attention to the man behind the curtain. It is the projection on the curtain that matters.

But the reactionary answer to the meaning crisis is clear: we can go back to the way things used to be, and in fact those ways are ordained by God and immutable, and they place ‘us’ on top, where we belong, even as we say we are submitting to them.

3.

In the reactionary ideological imaginaire, there is a binary choice between traditional values on the one hand, and anarchy and anomie on the other. If ‘traditional’ Christianity is displaced (even though it is actually a quite new form of Protestant fundamentalism), if gender roles are changed, then all hell breaks loose.

Like many conservative views, my main reaction to this is puzzlement. Because it is obviously and demonstrably false — and yet, maybe 100 million Americans believe it.

I experience this myself. I have all kinds of meaning in my life. I meditate, I practice psychedelic spirituality, my weeks and months are shaped by the Jewish year. I find meaning in opposing fascism, with the limited tools I possess. I’m very #blessed to be able to do meaningful work in journalism like this on the one hand, psychedelic humanities on the other. I’m insanely passionate about music and film; beauty moves me to tears, and I still go out a lot. I’m part of several remarkable communities of people I respect and love. And I’m a rabbi who loves my weird community of Jewish neo-pagans, BuJus, social justice warriors, and both/anders. I even wrote the first draft of this post while sandwiched between my husband and daughter on an airplane. The meaning crisis is not part of my personal subjective experience.

And that’s just me. In fact, practically everyone I know disproves the false binary between traditionalism and meaninglessness. Progressive religionists, sincere atheists committed to an ethics based upon compassion, activists who value empathy and demand it be put into practice, spiritual-but-not-religious practitioners, culture vultures, communities of care and connection — all these exist and create meaning and do many of the things that traditional religion does.

One of the insights of religious studies scholars over the last half-century has been to recognize that these ways of being may be understood as religious, but religious with a lower-case r. They are ways of ordering our lives and our communities around things we consider sacred, or beautiful, or of paramount (even ultimate) concern, but they do not depend on dogmas, myths, or the literal truth of sacred texts. Small-r religions have their rituals, their community norms, their core principles and beliefs. They serve as vessels for meaning and purpose. But they aren’t about how old the earth is, or convincing everyone that some beliefs are correct and others erroneous, or faith in an unseen deity. Often, those practicing small-r religion may not even like the word ‘religion’ and that’s fine. The point is only that it’s quite possible, with some intention, to experience some of the meaning-making of religion without it being Religion.

I’ve been living this way for thirty years. Here’s an essay I wrote about it in 2004. I don’t believe in traditional teachings about the anthropomorphic God or the truth of Biblical revelation — or, more specifically to Judaism, in the binding nature of religious law or the special status of the Jewish people. I am more inspired by those marginalized by religious authorities than in anything resembling orthodoxy. I don’t think everything happens for a reason, or the foundational objective truth of morality.

But I love ritual, holidays, the Jewish lifecycle, spiritual practice, the deep well of Jewish text and tradition, and the ‘weird religion’ which consists precisely of the parts I didn’t learn about in Sunday school. (Except for the weird parts that, in Judaism, are right out in the open, like the magical fruit on Sukkot.) I also love the rituals of earth-based spiritual practice, the teachings and practices of the Dharma, and the small-r religiosity of subcultures around the world. And while I’m often exasperated by Jewish communities, I do understand that I’m part of this tribe and it is part of me.

4.

But small-r religion seems not to have caught on. It doesn’t “stick” like Religion, it doesn’t have the same intensity or the same durable forms of community. I wonder if it will ever really compare.

I remember feeling this way many decades ago. Ideologically, my fellow travelers were in progressive, spiritually-minded, egalitarian communities. But the Hasidic prayers were always better. And more than that: for ten years I lived as a quasi-Orthodox Jew. I loved the strong communal bonds, the holistic nature of the religious practice, the depth of textual learning that could only come after years of experience. It was hard letting that go.

In contrast to Religion, which comes ready-made with communities and norms for deep engagement, small-r religion takes intention, commitment, and community. And it probably takes some level of education, privilege, and ability; probably the best critique of small-r religion is that it is an elite phenomenon. Not everyone has the interest, time, resources, ability, or skills to co-construct these worlds of meaning. Traditional Religion is meant for the many, not the few.

It’s also true that even spiritual practices like psychedelic practice, mysticism, and meditation don’t, themselves, ‘do’ these things. For example, psychedelic mysticism often lacks the structure, community, and language necessary for integration and long-term growth. This makes sense, because for the vast majority of historical psychedelic use — i.e., in indigenous communities — it came wrapped in cultural, communal, and religious contexts. Psychedelics were always a part of those contexts, not apart from them. Take those contexts away, and you don’t have the enduring forms of support, meaning-making, community-building, and integration. They don’t come automatically, which is why psychedelic spiritual communities exist. It takes commitment, which it’s harder to develop when people are not usually born into these communities; it’s something you have to be interested in and devote time and resources to.

So maybe it’s no surprise that small-r religions are small. Progressive Christian and Jewish denominations are tiny compared to non-progressive ones. And while non-religious ‘religions’ can be deeply immersive — I just took my daughter to Disneyland and got a glimpse of the fervor of Disney Adults — they often lack the structures and all-pervasive qualities that make Religion effective.

I don’t have some manifesto for how that changes. Maybe the meaning crisis will help institutional religions find their relevance again. Mainline Protestantism, Reform Judaism — these were once massive phenomena, and maybe they will be again as non-conservatives search for ways to make meaning for their kids and save them from the inferno of Andrew Tate.

But I don’t know if that can happen. Those parents are going up against Google and Meta and TikTok, and the sense we seem to have that these companies’ proprietary, exploitative, and rage-inducing algorithms are immune from regulation. They’re also going up against the hard realities of Gen Z: that except for the few, home ownership may never be affordable; that climate catastrophe may be inevitable; that AI will obviate the need for the majority of white-collar jobs. Having benign spiritual experiences may not be enough to counteract all of that. The climb seems steep.

But if anything can stand up to societal nihilism, it’s a 2000-year-old religion with libraries of moral theology and cathedrals on five continents. Maybe that’s what it takes. In a way, America is just like I was thirty years ago: the nice, progressive small-r religion just doesn’t have the power of traditional forms.

Still, I’m not giving up. It’s a very strange feeling to feel like I’ve solved the meaning crisis for myself, but that very few people are interested in my solutions. I love my religion with a lower case r, but will it ever scale to the point that it can challenge nihilism on the one hand, traditionalism on the other? I really don’t know.

Thanks for reading. Let me begin with an advertisement for the 2025 Adamah Meditation Retreat, which I’ll be co-leading next month in Connecticut. This six-day silent retreat combines insight meditation with non-traditional Jewish prayer and is a great example of the kind of contemplative small-r religious practice I love. (Non-Jews and Bagel Chasers are welcome.) If you use code JAY10, you’ll get 10% off the registration cost — which, incidentally, is only to cover room & board; the teaching itself is offered by donation.

Feel free to pass the discount code on to your friends and communities.

Meanwhile, some links:

The good news continues this week: Here’s

with the best summary I’ve seen of this week’s Epstein revelations, and the furious reactions they’ve caused on the Right. And here he is again with an analysis of the disastrous interview Trump did with Laura Ingraham, who usually fawns over him.I will probably be writing about this, but in the category of people I never thought I’d be recommending you read, here’s far-right conservative commentator Rod Dreher reporting on the pervasiveness of hard-core antisemitism among young MAGA apparatchiks in DC. This is required reading. Here’s

on the same thing.Since I use Penn Station almost every week, it was extremely depressing to read this excellent NYTimes in-depth investigation into why it sucks and probably will continue to do so.

See you next week and thanks to all my subscribers for your support and recommendations!

Small "r" religions like Jewish Renewal, for example, are dedicated to individual spiritual transformation. They cannot, nor do they claim to, drive vast social movements. They are entirely voluntary which means they don't have the power to hold people in institutional prisons like large, demanding fundamentalist groups. To be born into a fundamentalist Religion and decide to leave it is an enormous decision. People engaging with small "r" religions can come and go freely which means the Religion has much less power and influence over their lives.

Shabbat shalom