Firefly!

I miss the feeling of momentary, unambivalent joy.

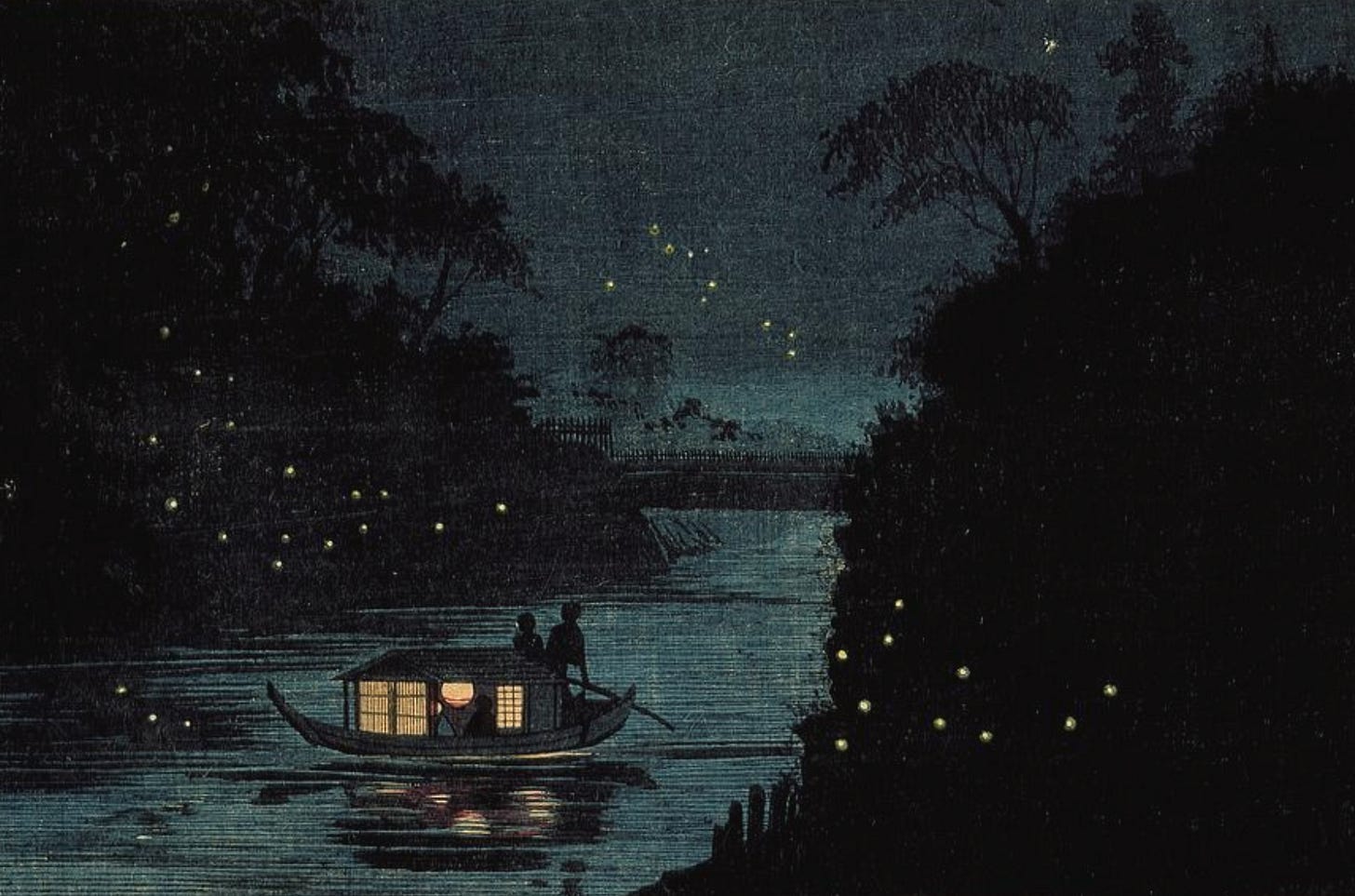

“Firefly!” my daughter cried in delight.

It was a simple moment, like countless others before it: my daughter, seven and a half now, spotting a firefly in a playground just after sunset. She ran over to watch it glow.

These are the years that parents get nostalgic about: she’s old enough to be a real person with opinions, ideas, and conversations, but young enough to still want to hang out with me all the time, to still love me unabashedly.

The only other people at the playground were a group of boys, aged around thirteen, who had a very different tone of voice. They seemed like good kids, but thirteen isn’t seven and a half. I doubted that they still felt childlike delight at fireflies, or that if they did, they’d say so out loud.

In 2025, having a child at this age is a very specific experience. On the one hand, she is largely oblivious to politics; she hates Donald Trump because he is a jerk and because he beat Kamala Harris who she loves, but she obviously doesn’t follow the day-to-day news. She provides an escape. When I’m with her, I can forget the world we’re living in, and the combination of fools and knaves who currently control it.

And yet, I can’t help feeling that I’m lying to her, creating this bubble of okayness, knowing that in just a few years, she will come to understand what I’ve been hiding from her. I often feel guilty about it — not the situation, but the misrepresentation. Won’t she be right to feel betrayed, as though I’d pretended the world is more stable and more beautiful than it is?

The truth is, I don’t know how to prepare her for the future: what life skills will be valuable, what emotional skills would be helpful, whether we should plan in a concrete way for living somewhere else if we can. For another year or two, I seem practically omnipotent to her, but pretty soon she’ll learn the truth.

My friends with boys are worried about the manosphere. It’s like a malevolent, poisonous pit, like the Sarlacc Pit in Star Wars, its gaping maw wide open. Kids spiral down into it through seemingly harmless entry-points — fitness influencers, sports heroes — and they sometimes never reemerge. I think of those thirteen-year-olds at the playground and I wonder, how many of them are already vulnerable, what if anything can be done to protect them… or us. How many of them are already viewing ‘extreme’ pornography online (most, according to data), how many follow TikTok influencers with odious or misogynistic views. How many grains of sand are left in the hourglass?

I feel the time slipping away; this very brief period in my daughter’s life feels fragile and transient.

For a certain kind of psychologist, spiritual practice is fundamentally about recapturing the innocent ecstasy of childhood. My daughter’s “Firefly!” to be sure, but before that, the inchoate euphoria of a baby held by the parent, the sense of wholeness and safety and love. Psychedelic ecstasies, sex, music, charismatic religion, art (making and experiencing), spirituality, flow states, the oxytocin rush of a football field or political rally, the self-annihilation of mysticism — we yearn for these experiences because somehow we remember them somehow, beneath our conscious minds, and we long to feel that way again.

Maybe, anyway.

I know in my own experience, it’s become a lot harder to feel that kind of joy in the last few years. I still have interesting spiritual experiences, but with the world as it is, it’s a lot harder to let go into them. Without drugs, it’s become almost impossible. I still experience happiness and pleasure taking a bike ride in nature, swimming in a summer lake, lighting candles as a family on Friday night, eating a delicious meal, seeing some drawing or craft that my daughter has created. But increasingly these joys feel brief and shallow. Like dreams disturbed by a sound outside, they can be ruined abruptly with just a thought of America.

I feel a little embarrassed that the state of the world impacts my emotional life in this way. It feels privileged, somehow, as if my own needs are so well-met that I have the luxury of feeling unhappy about martial law in Washington, climate suicide, or the erosion of the rule of law. Fortunate, privileged me.

I actually wish it were otherwise. I wish I could forget as easily as many (most?) people can. I have friends heading off to an awesome queer musical festival this week, but I’m not going, in part because it feels kind of gross to me. This is not an ethical judgment: there will be trans people at that festival who have it a hell of a lot harder than I do right now. It’s just how I’m wired, and I wish I were wired differently. Whether it’s regression to childlike joy or spiritual pneuma or just simple enjoyment, I’ve lost that ability, not out of political-moral responsibility but, it seems, simply out of temperament. I’m stuck in here.

I do still have access to other, quieter joys. As I’ve written in these pages, and in my book The Gate of Tears, there is a joy merely in the relinquishment of resistance to sadness. Once I surrender to what is, there is a kind of peace. There is the juxtaposition of the tragedy of this year with the beauty and stillness of this moment; as I write these words, sunlight plays on my desk, filtered through the shadows of leaves blowing in the breeze.

But that’s not the same as joyfully crying “Firefly!” I haven’t felt that way in months.

Not for the first time, I found, as I was putting this essay together, that Anya Kamenetz had just published something similar. Beginning with Brueghel’s “Fall of Icarus” painting, largely about how ordinary life often goes on oblivious to mythic-level, world-historic events, Anya writes that

This is some of us these days, eating, opening windows, lingering over coffee on the patio, putting on sunscreen… and sometimes stopping to scream at each other CAN’T YOU SEE WHAT IS HAPPENING!

Maybe if that music festival started with a group scream, I could get into it.

I’ve been thinking a lot, lately, about ordinary life in Nazi Germany, before the war really came home to people — when, for most Germans, life went on pretty much as it had before, just as it does for us now. Photos of this period have been hard to find. Here’s a nice collection of people getting married, kids having fun, interspersed with images of war and fascism. Here are some badly colorized home movies.

The point is, if you were one of the lucky ones, life went on. And maybe it’s that way for me right now. Even if the military patrols the streets of Manhattan, I live in the suburbs. Even if, just a few miles from my home, masked ICE agents kidnap lawful residents of Newark, I’m here writing my Substack. Although I can’t seem to write a ‘pure’ essay about the transience of youthful joy without politics intruding upon it.

Anya also quoted W.H. Auden’s poem Musée des Beaux Arts, in part based on the Breughel painting. I think it ma be the most apt rendition of Summer 2025 that I’ve seen, appropriately since it was written about Paris in 1940:

Musée des Beaux Arts About suffering they were never wrong, The Old Masters: how well they understood Its human position; how it takes place While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along

This seems wiser than my inability to hold gladness and dread together, even if it is also a kind of obscenity. One person suffers, another opens a window. This is not inhumanity; this is how humans have lived for thousands of years. The poem concludes:

In Brueghel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry, But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky, Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

I find myself wishing: May it be so.

Thank you for subscribing and supporting this publication. If you find yourself resonating with the thoughts in this week’s newsletter, consider commenting. Let’s build community together.

Here’s some political stuff I’ve been reading this week:

Jacob Abolafia did a great long-form piece in The Point about how the tolerance for violence in certain parts of the Left (especially the pro-Palestinian left) reflects a kind of absence of real politics. It is not an anti-Left piece — I don’t recommend those. It’s a thoughtful analysis of where progressive politics fails and a kind of vacuity emerges.

Paul Krugman continues his hot streak with “The Political Economy of Incompetence,” a reminder that fascism depends on morons who work for bad guys.

Here’s a rather informative and depressing short take on “Love Island Face” and why people under 35 might not regard it as the horrible abomination that it is.

Couple of excellent New York Times op-eds this week: Michele Goldberg on the real-life disillusionment of a trad-wife influencer, and economist Roland Fryer on an elegant mathematical solution to gerrymandering that I’ve been dreaming of, without his expertise, for years.

If you value your mental health, I don’t recommend you read this essay in Common Dreams entitled “Trump Wants to Turn America Into a Police State.”

Here’s an update on last week’s bombshell report on the Democratic Spam Machine ‘Mothership’: some progress is being made.

Finally, I was unaware that Stephen Miller claimed that “Americans, not illegals” built our nation’s great works of architecture (I mean, I guess technically slaves are not ‘illegals’) but here’s a complete takedown of that racist crap at The Big Picture including the fascinating (and unknown-to-me) history of Native Americans building America’s skyscrapers. Remember: no permits, visas, or anything else were required to enter America prior to 1917 if you were white.

That Auden poem has been one of my favorites since I first encountered it as a high school sophomore.

And I still smile at puppies and rainbows and sunsets and root for my teams. And I have friends with who I can and will rant and cry and laugh.

For what it is worth, as a child I hated being lied to and I hated being patronized because I was younger. Life is never all sunshine and lollipops and roses. If I did not understand all that was being said or shown, that was okay. And if I did, that was okay as well. We raised our son the same way and he grew to be a level headed, compassionate, and accomplished adult.

There is no one correct path.

Thank you for this. I've been feeling this same way and wondering when I got so morose.