1.

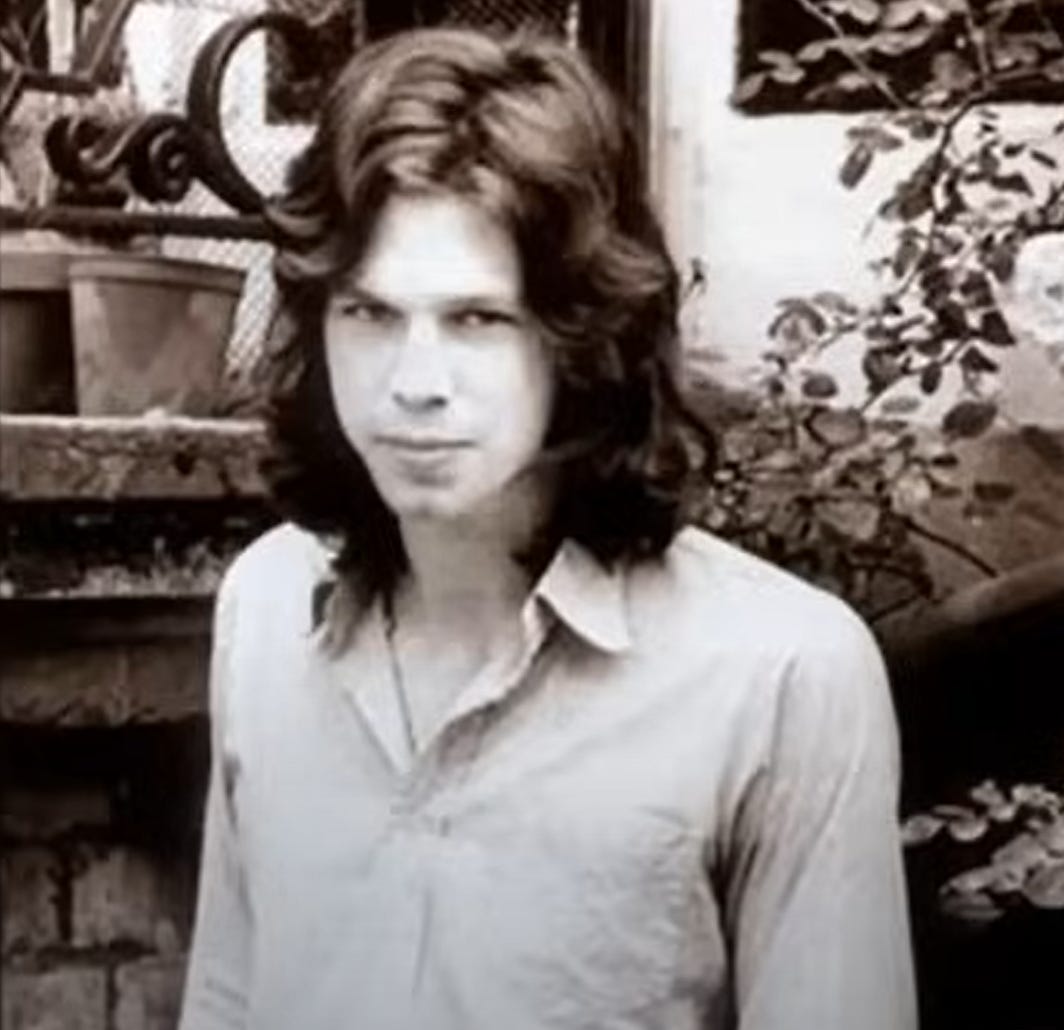

Nick Drake’s most devoted fans have a strange way of speaking about him. Music critic

, writing in his Substack last week, felt the need to begin his review of a new box set with “Full disclosure: There’s no album I feel a greater connection to than Nick Drake’s 1969 chamber-folk debut Five Leaves Left.” And in Hermes’s interview with Ben Harper, the musician recalls how he and the late actor Heath Ledgerused to sit up and play Five Leaves Left over and over, dissect every word of the entire record and talk…. We would just go deep. Heath worshiped Nick… It was one of the centerpieces to our friendship.

There is devotion, and then there is Nick Drake devotion.

To most people, Nick Drake (1948-1974) is chiefly known as the singer in a Volkswagen commercial — a beautiful, poignant Volkswagen commercial, actually, which made me cry the first time I saw it, because there was Nick Drake singing on my television set, and the ad seemed to get it, with its story of a small group of friends who forsake a loud bar for a quiet drive under the stars.

But to some of us, Nick Drake is an intimate friend who understands us in ways we do not understand ourselves. All this to say, this is not an objective review of the new Nick Drake box set, The Making of Five Leaves Left. It is, if I’ve pulled it off, an essay about longing, music, sadness, pain, and beauty.

2.

Sometimes the right music comes at the right time. And sometimes it comes again, decades later.

I first heard Nick Drake’s music in 1994, on a friend of mine’s barely-functioning car radio. I wasn’t persuaded at first, but eventually I bought one of his albums, and then another, and then the third. (They were hard to find, and in those pre-streaming days the thrill of finding a rare album was part of the joy.) I listened to them over and over. All are tinged with sadness, but the third album, Pink Moon, recorded while Drake was in a deep depression after the failure of his musical career, was beautiful in a way I hadn’t encountered before. I love sad music: the third Velvet Underground album, Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks. But this was so exquisite while also being sad. It was so beautiful. It made me cry, and when I wasn’t able to cry, it kept me company.

I knew the music before I knew Nick Drake’s story, which is easy to romanticize into a Van Gogh narrative of a brilliant, sensitive artist unrecognized in his time, though of course it wasn’t really just that. Born into an upper-middle-class British family in 1948, Drake taught himself guitar as a teenager, inventing countless alternate tunings (I’ve played them; they’re complicated) to create a sound that is grounded in English and American folk traditions but is inflected by jazz, bossa nova, and, we now know, from the showtunes that his mother Molly used to play on the piano. (Molly Drake’s home-recorded music was released a few years ago and carries some of the beautiful pathos, and haunting melodies, of Nick’s.)

Nick went off to Cambridge in 1967 and became that amazingly talented young man who played folk songs on his guitar. (In a weird coincidence, during my year in Cambridge 25 years later, I lived downstairs from an amazingly talented British folk musician also named Nick.) His voice was beautiful — androgynous, delicate, free from affectation and frill. But he was shy: he hated performing in public, and his classmates mostly have said that no one really knew him.

Yet on the recordings in The Making of Five Years Left, there’s a fair amount of Drake talking with his friends about how he imagined his songs might be arranged, and he sounds more normal than this description might suggest. He’s a shy British guy, reserved but with clear opinions. Actually, there was a lot of hope. Drake was signed to a record deal at age 20, and developed his first album in the midst of the burgeoning British folk scene; Fairport Convention’s Richard Thompson plays on one track.

But it was not to be. Five Leaves Left went nowhere — in fact all of his albums combined sold fewer than 4,000 during his lifetime. It didn’t help that Drake was unwilling or unable to tour in support of the record, but the music, too, was hard to pin down. It wasn’t sentimental folk, wasn’t quite Simon and Garfunkel pop-folk; the lyrics were sophisticated, sometimes inscrutable, the melodies defied folk music conventions. The instrumentation was classically-inflected, the chords somehow both major and minor at the same time (thanks in part to those alternate tunings). There often weren’t discernible choruses or hooks; the structures were unconventional. Five Leaves Left obviously wasn’t a mainstream pop or rock record, but it didn’t fit in the folk world either.

Drake and his producer Joe Boyd tried again with a more pop/jazz-oriented and orchestrated follow-up called Bryter Layter, but it, too, failed to make an impact despite all the backing vocals and production. (Belle and Sebastian would find success with this sound 25 years later.) The few reviews were mixed to negative.

Nick fell into a deep depression, only partly responsive to medication. He left London, moved back home with his parents, rarely leaving the house. Somehow, in the midst of it, he recorded Pink Moon, released in 1972, and had started a new collection of songs. But on November 25, 1974, he died of an overdose of the antidepressant amitriptyline (almost surely intentional; there were 35 pills found in his stomach). He was 26.

3.

As I played Nick Drake’s music alone in my room, his voice and guitar became the soundtrack to my loneliness. Back in the 1990s, I was closeted, sad, and above all lonely. Unlike Drake, I was a high-functioning depressive: I was in law school in those years, then clerking in Washington, D.C., then co-founding a tech company in New York. On the outside, I had a great life. I had friends, some of whom are still my friends today (hello, Dan), and compared to now, it was a great time to be alive.

But I was hollow. I felt like my life was disappearing in front of me. I wrote a never-to-be-published novel called The Architecture of Solitude, but I couldn’t publish it because the character was closeted and so was I. It wasn’t only the closet — I was also an introvert with social anxiety who liked weird films and mysticism. But it was at least partly that.

Like many solitary young people, I found comfort in nature, in the incipient spirituality that comes from walking in the woods alone, listening to the breezes and streams. As one of Drake’s lyrics says

I was born to love no one No one to love me Only the wind in the long green grass The frost in a broken tree

Or as Langston Hughes wrote in a poem that still shapes my self-consciousness today:

Sometimes a crumb falls From the tables of joy, Sometimes a bone Is flung. To some people Love is given, To others Only heaven.

Reading these verses now, I imagine they can seem a bit overwrought, though perhaps the lyricism of Hughes’s poetry and haunting melody of Drake’s music rescue them from being maudlin. Be that as it may, they embody who I once was. The Hughes poem was the seed of a book I wrote, and then rewrote, called The Gate of Tears: Sadness and the Spiritual Path, about the redemptive quality of sadness. I’ve performed the Nick Drake song “Saturday Sun” many times over the years, and wrote several songs of my own as ripoffs of homages to his work. The embrace of the beauty of sadness, expanded to the basic mindfulness teaching of accepting whatever is present in the mind, heart, and body at a given moment, is at the core of how I understand spiritual practice.

But the identification goes a bit further.

4.

I don’t have a “theory” that Nick Drake was closeted and gay, as I was. I’ve read one of the biographies of him, and pored over comments from his sister, the actress Gabrielle Drake, and the consensus is that we don’t know what his sexuality was, and probably will never know. He was, at least after age 20 or so, painfully shy, anti-social, and by all accounts asexual. That may have to suffice: asexuality is, of course, itself a sexual identity, though Drake died decades before it became embraced and celebrated as part of the queer continuum. So maybe that’s it.

But I hear and read Drake’s lyrics through my own experience. I hear his melodic “androgynous” voice and perceive someone who is not a heterosexual man, perhaps not even a cisgender man. I hear the major and the minor together. I resonate with his depression and with the sense of defeat he must have experienced after the failure of his albums. All of the love that I experienced for a decade of my adult life was unrequited and unfulfilled; if nothing else, I recognize that too.

And then there are the lyrics. Here’s the beginning of “Time Has Told Me,” one of his better-known songs that appears in four iterations on the new box set:

Time has told me You're a rare, rare find A troubled cure For a troubled mind And time has told me Not to ask for more Someday our ocean Will find its shore So I'll leave the ways that are making me be What I really don't want to be Leave the ways that are making me love What I really don't want to love

And its last verse:

And time will tell you To stay by my side To keep on trying 'Til there's no more to hide

Again, I know these lyrics admit of multiple interpretations. But these themes of secrecy and disclosure, of yearning to stop living a false life — to “leave the ways that are making me love/what I really don’t want to love” — are deeply familiar to me. I speculate that the subject of the song is a close friend (“time has told me not to ask for more”) for whom the narrator still yearns (“someday our ocean will find its shore.”

I also see how these lyrics might reflect Drake’s life, and how even in 2025 I’ve had arguments with people who say Walt Whitman wasn’t gay either.

There’s also what there isn’t in Nick Drake’s lyrics. There are no conventional love songs or sexual innuendos. There are no romantic lyrics about “she” and “her.” There are plenty of songs about women, but their subjects are mysterious and magical, not sexual. For example, “The Thoughts of Mary Jane” – the box set has a gorgeous demo recorded in a Cambridge dorm room in the Spring of 1968 – begins this way:

Who can know the thoughts of Mary Jane Why she flies or goes out in the rain Where she's been and who she's seen In her journey to the stars Who can know the reason for her smile What are her dreams when they've journeyed for a mile The way she sings and her brightly coloured rings Make her princess of the sky

Likewise, “Man in a Shed” — more pensive in the early demos than on the jaunty final release — starts as an unrequited love song between a man who lives in a shed and a girl who lives in a “house so very big and grand.” But the song ends with Drake turning them into characters in a parable. “The man is me/and the girl is you,” he says, imploring the subject of the song, “Please don't think I'm not your sort / You'll find that sheds are nicer than you thought.” Is the queer reading of this lyric the only possible one? Obviously not. But it is still so striking that across his three albums there’s not a single song addressed to a woman. It reminds me of R.E.M.

There are other suggestive lyrics here and there. “At the Chime of the City Clock” has a verse that goes “The city clown/ will soon fall down / without a face to hide in. / And he will lose / if he won't choose / the one he may confide in.” Again, longing to confide in someone; again, fear of being exposed. “Things Behind the Sun” urges “Open up the broken cup /Let goodly sin and sunshine in / Yes that's today.” Sunshine — always present as a symbol of happiness, consolation, love—paired with “goodly sin.”

Ultimately, what I hear in Nick Drake is a longing — a longing for meaning, solace, love, connection, transcendence, or mystery, whatever it is that seems to lie beyond our reach, even as others possess it thoughtlessly. I may only be imagining that he and I share the root of that longing, but I know that we shared the longing:

Don't you have a word to show what may be done Have you never heard a way to find the sun Tell me all that you may know Show me what you have to show Won't you come and say If you know the way to blue?

We don’t need to decode what “blue” means here. It doesn’t have to have a fixed meaning. We know what it means even if we don’t know what it means.

5.

Sometimes the right music comes at the right time. And sometimes it comes again, decades later.

I hadn’t intended to write about The Making of Five Leaves Left. I wasn’t sure I’d even listen to its 32 alternate versions of songs I’ve loved. But in addition to being a revelation —the early demos are so immediate, you feel like you’re sitting in the dorm room with him — it was medicine I didn’t know I’ve needed. Because while I’m not a lonely, closeted twentysomething anymore, I am sad these days. I’m living through things I never thought I’d see; whether we call them authoritarianism or fascism, genocide or war crimes, at this point I don’t fucking care anymore, I just cannot believe in the everyday reality we are living through, and it is affecting me. And as I mentioned last week, I’m still recovering from my accident last month, with less energy than I usually have and a fairly empty summer schedule as a result. It’s not clear to me what authentic joy looks like in 2025, or whether I want it to look like anything at all. I’m just not sure it’s possible for me right now. Not unlike thirty years ago, in a way.

Rehearing Nick Drake’ voice brought me home to this sadness, connected it to this moment in our public lives. It feels better to accept sadness than pretend to be happy; better to embrace weirdness than pretend to be normal. Ah, I remember, I felt my heart saying as I listened to these old tracks in new contexts. It reminded me, too, of the vitality of those years nearly three decades ago — how in touch I was with my own heartbreak and loneliness. I don’t want to return to how I was then; even today, I am happier now. But there was an immediacy to life, albeit rendered in pain.

In several songs, Drake makes use of the longstanding symbolism of daytime sun (light, joy, love) and nighttime moon (darkness, sadness - even, in “Pink Moon,” vengeance). In the the last song on his last completed album, there emerges a kind of synthesis between the beauty of the day and the night, the sun and the moon, which offered me, today, a modicum of integration, even of hope:

A day once dawned, and it was beautiful A day once dawned from the ground Then the night she fell And the air was beautiful The night she fell all around So look, see the days The endless coloured ways Go play the game that you learnt From the morning

Here’s

on Nick Drake from a few years back. Here’s Gabrielle Drake talking about him a few years before that.Here’s my recent article on how you can make the Bible say anything you want it to, and why doing so is maybe not a good idea.

Gaza in NPR, Haaretz, and Haaretz again (on the “G” word).

No Trump stuff in the newsletter this week. Please do anything you can to raise awareness about the threat Emil Bove represents to democracy. Otherwise, please listen to Nick Drake instead.

I’ve been in love with Nick Drake’s music for most of my life. I first stumbled onto him in the mid 90s at one of those old record store listening stations. I pressed play on Way to Blue without knowing what to expect and was instantly transfixed. I bought the CD that same day and played it obsessively. I wouldn’t even call myself just a fan, more like a devotee. This music is part of the deep soundtrack to my life. Thanks for sharing this. I’m listening now and already feel like I’ve slipped into another world.

This is a beautiful essay, inspired by beautiful music. I've been listening to the box set this week and reading the book that come with it. I, too, didn't think I was going to write about it. Then I thought I would. And now I think perhaps I won't, after all, in part because pieces by you and others have it so well covered. Or rather, I will write (have done so already), but perhaps not publish.