Until last week, I thought I knew what a ‘ceasefire’ was. It is ceasing fire. And since in the current war, most of the fire is coming from the Israeli side, it mostly means that Israel should cease its operations in Gaza, which as of this writing have killed more than 8,000 people.

Recently, though, it’s become clear that the word is not so simple.

First, Hamas is also firing – since October 7, they’ve launched 7,400 rockets into Israel. Most of these are either intercepted by Israel’s Iron Dome defense system, or misfire, or fall in open areas. There is no comparison between the deaths caused by Israeli bombing and the deaths caused by Hamas’s rockets, but still, the latter still terrorize the Israeli population, and they are “fire,” right?

So already, a ceasefire really means a reciprocal, negotiated ceasefire — otherwise, the fire hasn’t ceased. Hamas would have to agree to stop doing something, which it’s not clear it will do. And in any event, based on previous Israel-Hamas skirmishes, there is a strong reason for skepticism that such an agreement would last more than a few minutes. In past conflicts, the slightest provocation – someone approaches a guard tower and is shot, for example – leads to immediate escalation. Surely that would happen again now. The “ceasefire” would be a blip. It wouldn’t allow refugees to return home, or anything like regular life to resume.

And then there are the hostages.

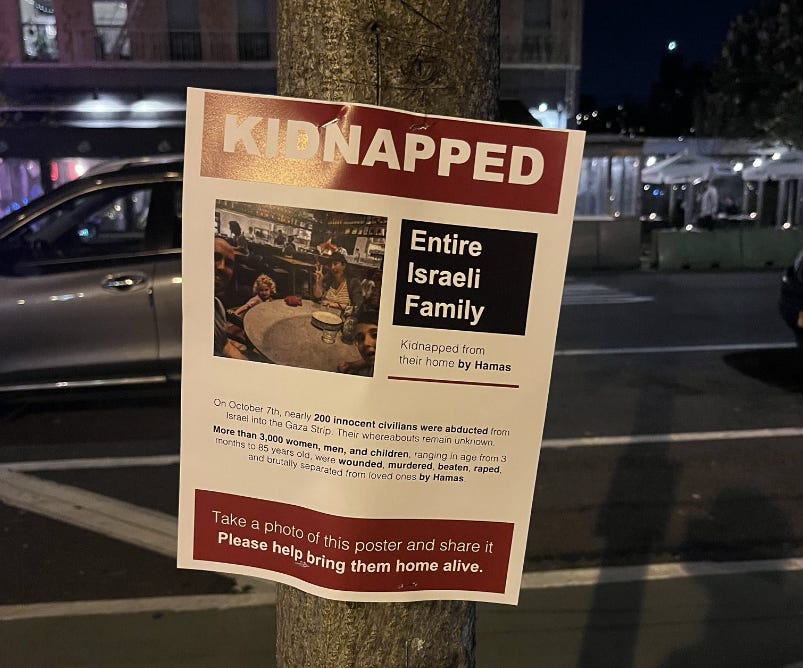

Probably for most protesters, a ceasefire is about ceasing fire, nothing more. Presumably, negotiations could then begin around releasing the 220 hostages Hamas kidnapped on October 7 and is now holding in tunnels across Gaza, which it paid for by diverting aid meant for the Palestinian people.

But wait a minute. In what sense is it a ceasefire when one side is holding 200 kidnapped civilians at gunpoint? If any of them tried to escape, they’d be “fired upon” immediately. Doesn’t “cease fire” mean “put down your weapons”? Holding these people hostage is an ongoing act of violence.

Moreover, a ceasefire first and negotiations second is morally and politically bankrupt. It rewards a terrorist organization for kidnapping 220 civilians, which is a war crime, and it encourages other bad actors to do likewise. It is a gigantic moral hazard, encouraging every terrorist organization to do what Hamas just did.

Granted, Hamas regards the 4,450 Palestinian “security prisoners” in Israel to be prisoners of war. And Yahya al-Sinwar, the head of Hamas in Gaza, has said that Hamas is open to a full exchange of “the release of all Palestinian prisoners from Israeli jails in exchange for all prisoners held by the Palestinian resistance.” Some kind of prisoner exchange may yet take place.

But for Israel to cease operations before entering into that process would be to abandon what little leverage it has in such negotiations — which, again, are for the release of Israeli civilians in exchange for Hamas guerilla fighters. No negotiator, let alone a state, has ever done something this antagonistic to their own interests. It’s absurd that this is even being contemplated.

Indeed, Israel’s starting position is the polar opposite: release all the hostages, and then we’ll negotiate a ceasefire. Of course, Hamas is not going to agree to that for the same reason Israel won’t agree to the reverse. Both sides have something the other side wants. That’s how negotiations work. No one enters a negotiation having first given away what the other side wants. That’s not a ceasefire; it’s a surrender.

The intuitive appeal of “ceasefire” is obvious. But as soon as you start looking into the details, the obviousness disappears and it’s clear that different people mean different things when they use the word.

To be sure, there’s still an important difference between supporting the negotiation of a ceasefire that includes the release of hostages on the one hand, and Israel’s stated goal of utterly destroying Hamas on the other. But there’s an even bigger difference between that nuanced position and what I think most activists really mean when they demand a ceasefire.

Which is part of the point.

I’ve written at length about the use of the term “genocide” to describe Israel’s actions in Gaza. I am certain that those actions do not qualify as genocide under international law. But it’s also true that our language lacks the vocabulary for the horror that is taking place: thousands of innocent people with nowhere to run, being bombarded by a powerful military, knowing they and their children could die at any moment. That isn’t “genocide” but it is something horrible, is it not? What word does describe it?

“Ceasefire” seems similar. Conceptually, it’s incoherent, but it does give voice to the emotional, moral response to human suffering, which all of us, regardless of politics, ought to have. Cease the fire. Just make it stop.

If only things were that simple.

Hi, friends and subscribers. Thanks for your overwhelming show of support for this new project. I didn’t expect its launch to coincide with a horrifying conflict, but I’m glad this work has connected with so many of you. Please comment, like, share, and, if you feel moved, subscribe. That’s the business model.

As we move into what feels like the next phase of the conflict, I’m balancing continued writing about the war with doing, well, other things.

In Rolling Stone, I argued that while Hamas bears sole moral responsibility for what’s happening, twenty years of right-wing Israeli policies have brought us to this point. This is Bibi’s war.

And in the Forward, I argued that advocates harm the cause of human rights by stretching the meaning of the word “genocide” to describe Israel’s actions. This week, I’ll have another piece in the Forward responding to critics of the first one.

Also, tonight, October 31, I’ll be on News Nation at around 7:30pm ET, explaining on conservative cable news why some LGBTQ people are standing in solidarity with Gaza, and why that’s a demonstration of courageous principle (even though I disagree with it) rather than foolishness. Wish me luck.

Meanwhile, this week I’m also recording the audiobook version of my forthcoming collection of short stories, The Secret that is not a Secret (pub date of December 5) and planning New York Insight Meditation Center’s fall benefit featuring Leslie Booker and Dan Harris (taking place November 14).

Lastly, I'm happy to share that I have a new academic position as a Field Scholar at the Emory Center for Psychedelics and Spirituality.

ECPS is doing amazing work in this emerging and fast-growing field. As described on its website, it is “the world’s first center to fully integrate clinical and research-based expertise in psychiatry and spiritual health to better understand the therapeutic promise of psychedelic medicines.”

What am I doing with all these brilliant scientists and clinicians, since I am neither? As a Rabbi/PhD with two decades of work in meditation and contemplative practice, my hope is to contribute to ECPS's work on how psychedelics can be of profound religious and spiritual significance, and also do harm if not held carefully. Many people encounter these substances in medical contexts, for example, only to have powerful and perhaps unexpected spiritual experiences that may be very challenging for them. Because the field is so new, clinicians lack adequate protocols for doing this work that are attentive to different religious contexts and settings. There's also been amazing, pioneering work on psychedelics and religion that can be enriched by more engagement with scholarship in religious studies, theological discourse, and diverse voices from multiple backgrounds and traditions. These are some of the areas where I hope to make a contribution. I'm joined in this work by my fellow clergy-PhD, the remarkable Rev. Dr. Jaime Clark-Soles, a professor at Southern Methodist University and Baptist clergy, and hopefully more to come.

It's been over thirty years since my first psychedelic experience in 1990, and these medicines have long been in the background, usually unspoken, of the Jewish and dharmic spiritual traditions of which I am a part. And while the current moment of enthusiasm ought to be tempered with real attention to issues of power, access, and the potential for harm, still I am amazed and a little cosmically puzzled at the transformation that is now taking place. I look forward to writing and teaching more openly about all of this, and am grateful to George Grant, Boadie Dunlop, Roman Palitsky, and the team at ECPS, as well as to my many fellow Jewish, Buddhist, and spiritual-of-all-flavors psychonauts. In a dark time, it is nourishing to have a glimpse of Light.

I appreciate the good questions. A ceasefire right now = more Hamas killing. I think the Far Left/Progressives/very liberals, whatever you want to call the more polarized side of the Left/Right equation, is facing a reckoning this horrible war is catalyzing, perhaps for the best. The Far Left, like the Far Right, is mired in orthodox groupthink that is now being revealed as having lost the thread of morality and even just plain common sense. As an example, the rise of Queers for Palestine, as if there are LGBTQ rights in any Arab country, let alone Gaza, is a clear cut demonstration of the nonsensical nature of the far left discourse. Please keep writing!

Thank you Rabbi/Dr Jay for grappling with some thorny issues. I can see you're trying to be open and struggling to find a way forward-- thank you. One thing that seems not at all complex to me is the evil of the October 7 massacre and our concurrent obligation to stand up to evil and call it out. It stuns me that I've seen no one else in the meditation community condemn the pure evil we witnessed by Hamas against babies, children, Holocaust survivors. Please tell me I'm wrong and I've just missed the statements of IMS or any of the stellar meditation stalwarts (Sharon Salzberg, Jack Kornfield, Joseph Goldstein, Jon Kabat-Zinn, Pema Chodron, Sylvia Boorstein, Diana Winston) out there. Where is everyone?