The Ascent of Chana Rivka Kornfeld

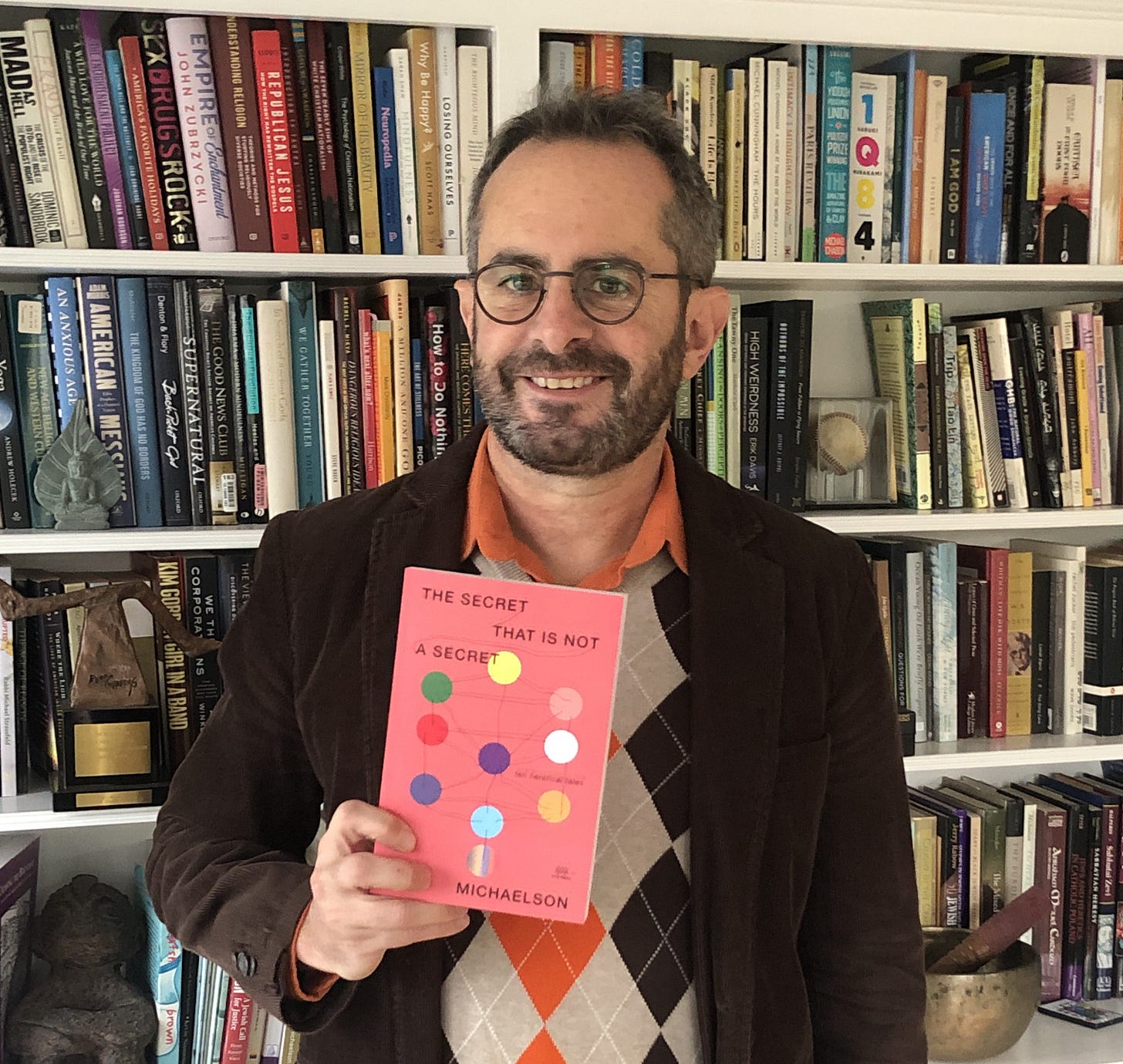

from my today-published book, "The Secret that is not a Secret"

It’s publication day! My tenth book - and first of fiction - is now out in the world. We’ll be celebrating tonight with an online performance/reading/conversation - I’ll be joined by the all-brilliant Jericho Vincent, Eden Pearlstein, and Shir Meira Feit. (It’s free, but advance registration is required here.) I am deeply grateful to the many folks at Ayin Press for making this long-simmering dream a reality, and to so many of my teachers, fellow writers, friends, and family members who have made the whole thing possible.

I don’t expect that this work of heretical, mystical literary fiction will reach as many people as, I dunno, my CNN appearances or guided meditations on YouTube. But (ironically, since it’s fiction) it’s the closest expression of “me” of anything I’ve written: the spirituality, the sexuality, the imagination, even, a little bit, the politics.

The story I’ve decided to share here, previously unpublished, sits at the same nexi as does this newsletter: politics/spirituality, eros/thanatos. Of course, I wrote it long before the current war, but its themes seem all the more real today. I hope you enjoy it, and thanks to you, readers, for enabling my work to be sustainable! -jm

The Ascent of Chana Rivka Kornfeld

I am here and not here.

I feel the cold tile of the floor, the same tile we all have in this part of Jerusalem. My husband Eliezer is looking over me. I can also hear his thoughts. He is seeing the brown shingles of a house in Plainview, Long Island, where he had lived as a child, thirty years ago. He is remembering how he had reacted when the other kids didn’t play according to the rules; he is seeing himself smash the buildings they had built against his wishes.

What a strange thing has taken place. I have a television on top of me.

Eliezer is looking down at me, a thin coat of sweat under his arms, around his shoulders, and on the crown of his head, beneath his thinning hair and under the knitted kippah fastened to it. He had been watching, as always, the news. He believes that the conflicts engulfing the Jewish people are the birth pangs of the Messiah, the advent of a time of war and confusion before the Temple will be rebuilt and the enemies of Israel cast out. Soon, he told me once, maybe this summer.

Our lives have changed. Mine is about to end. Eliezer was wrong: the true redemption wouldn’t have to do with horsemen and apocalypse. It would be so secret that few would even know it had occurred. It would be so subtle that only the attentive could perceive it. For most, the malls would remain open; everything would be as it was. For those few who perceived, all would be new. This was the promise of the forgotten Messiah of the past, and his faithful believers.

“The leftists,” Eliezer had shouted, “the antisemites, the perverts.” Eliezer was in a rage, as he had been many times before. I came into the room and I saw that he had gotten up off the sofa and was standing in front of the flat screen of the television, picking it up as if to smash it like Moshe with the tablets, except this lasted only a moment, because he didn’t see me in his rage and I couldn’t move away in time and the sharp edge of the television hit me instead and knocked me to the floor and I tasted blood and the screen did drop and shattered and the shards scattered and with them the light. I am here and not here.

Perhaps there is a One who is responsible for all that happens. Eliezer’s anger, the politicians, the television news. The moment was a confluence of events, a chance encounter of a thousand causes. Some would call it an “accident.” I heard Eliezer use the word in his mind. It was an accident. As if to deny that there is a judge and justice. Blessed be the true judge, I say for myself. And was it an accident, that I stayed with him through these years of childlessness and endless, spiraling anger? All his fitful rustling in bed, his complaints about his pointless job at the call center, his shouting at me or the neighbors or the news. I stayed because there was no better option. Even now I can feel the anger rising within him, as if this was something that had happened to him instead of to me, or that it was the leftists’ fault, the antisemites, the perverts.

I see Eliezer as a little child, five years old, teased and beaten up by the older boys. I see him as a teenager at the moment he learned his friend—really just an acquaintance—had been killed by a terrorist. All these moments congeal in him: the pure, hot fire of rage. I join the list of his victims: doors, appliances, dishes, computer keyboards, glasses. This coursing energy: this really is something that happens to him. It takes him over, like a dybbuk or an ibbur. Eliezer is remembering a toy truck. There was something wrong with it—it wouldn’t roll straight, or Eliezer had tripped on it—and he took the truck into his hands and smashed it on the floor, over and over again, until finally, a small plastic piece broke off. Small, but crucial, because now the truck wouldn’t roll at all. It was junk. So Eliezer threw it against a wall, making a mark on the wall (for which he was spanked later) and then took it into his hands and broke it into small pieces. He was alive then, as now. He was made in God’s image, capable of creation and destruction. If anger is idolatry, as the sages of blessed memory say, then who is the god it makes in its place?

When Eliezer and I first met, we were only just out of college, each in Israel on separate yeshiva programs. He had such a brilliant intensity, not like the boys I had dated in high school and college—wimpy, effeminate Modern Orthodox boys with their thin-rimmed glasses and pale complexions. Eliezer was direct, serious, certain. He would quote Rav Kook, or Jabotinsky. He had so much vitality. And I knew that if I waited much longer, the quality of men would decrease. I wondered if his intensity would ever translate into cruelty. But the heart can deceive the mind when it wants enough.

Soon after we met, Eliezer and I went for a hike in the desert, down near Eilat, the red mountains, the open valleys dotted with acacia trees. We saw school groups hiking, singing. It was lovely, a taste of the world to come. Eliezer, his submachine gun banging against the side of his thigh, seemed jubilant. He said, if I remember correctly, “The most beautiful love isn’t romantic love. ‘Romantic’—it’s an invention of the Romans. It’s the love of our land, our people, and Hashem. This love is what unites us as Jews, it is ahava in its truest form.”

At the time I found this inspiring. I was there but not there.

And when we discovered that I could not bear children, I felt Eliezer’s anger, for the first time, directed at me, even as he said outwardly that this was God’s will, and that we would accept this decree. He even said to me, once, that since we were no longer fulfilling the mitzvah of pru urvu, that his only obligation was my pleasure.

But it seemed to me that without children, we had lost our sense of purpose. What was the point of this fruitless union? What was my purpose on Earth? Each of us coped in different ways. I turned to spirituality. I went to see several tzaddikim, ostensibly for a segulah to help me become pregnant, but really, since I knew that was impossible, to taste the sparks of holiness that resided in these places. As a woman, many paths were closed to me, but these were open.

And I discovered, by the graves of the rabbis, and in the courts of living miracle-workers, an entire world apart, filled with the scents of burning hyssop and incense, suffused with a kedusha that Eliezer’s world scarcely knew. The women I met in these places taught me of the old ways, of herbs and amulets and secret things, of magical remedies and spells, incantations to attract angels and repel demons. It was astonishing to me, what could be permitted.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Both/And with Jay Michaelson to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.