Psychedelics and Judaism: New Skin for the Old Ceremony

Did my ancient Hebrew ancestors use psychotropic substances? Probably not, but the grammar of the visionary experience is similar.

These Are Days

The conversation between Jews and psychedelics is thriving.

In the last half century, American Jews have been all over psychedelic spirituality, culture, and medicine, from Allen Ginsberg and Richard Alpert/Ram Dass to Julie Holland and Rick Doblin, Leo Zeff to Ethan Nadelmann, Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi to Baruch Thaler z”l, Jefferson Airplane (3/5 Jewish!) to Phish, The Fugs to Seth Rogen.

More recently, with the advent of the so-called ‘psychedelic renaissance’ there has been an effulgence of Jewish psychedelic thinking — here’s a great conversation between Madison Margolin and Natalie Lyla Ginsberg, for example, and here’s one between Professors Melila Hellner-Eshed, Sam Shonkoff, and me — and lots of Jewish psychedelic doing, which for obvious reasons I’ll leave unspecified. There are, to my knowledge, psychedelic circles among secular Jews, Hasidic Jews, anti-Zionists, right-wing Zionists, Jewish Renewal types, OTD people, hipsters, professors, rabbis, artists, environmental activists. There’s a Jewish psychedelic organization, Shefa, which in addition to integration circles of all kinds is co-running a large-scale study of Jewish attitudes toward psychedelics being done by Emory University, where I am affiliated, and a class series starting next month called ‘Judaism is Psychedelic.’ It’s a busy time.

“What’s with all the Jews trying to legalize marijuana?” asked Richard Nixon in 1971, continuing, “It’s because they’re all psychiatrists.”

I’ll just leave that here as a koan.

One question that often gets asked is how long this “conversation” has been going on. There are some who believe that the answer is, well, millennia. They cite provocative passages in the Bible, Talmud, and Jewish mystical texts. They talk about etymology and chemistry. They point to archeological evidence of cannabis residue and (just revealed) Syrian Rue in Egyptian fertility ritual implements.

I am, as yet, unpersuaded by these claims. But I think it’s still possible, and useful, to look to the Jewish past for precedent, inspiration, guidance, and meaning for the Jewish psychedelic present and future. I think Jewish psychedelic use is, to quote Leonard Cohen, a new skin for the old ceremony.

2. Ancient Ayahuascas

I am sympathetic to the effort to find evidence for psychedelic use in the Jewish past. If one has some emotional or spiritual tie to Judaism, it’s natural to ask how this powerful spiritual experience does or does not fit into being Jewish. Are these experiences similar to the peak spiritual experiences described in sacred text? Orthogonal to them? Or perhaps misdirected, evil, wrong, avodah zara, or otherwise treyf?

Moreover, if one has psychedelic experience, then when one looks at visionary mystics in the Bible – Ezekiel, Daniel, Elisha, Isaiah – as well as in the Talmud, Kabbalah, Midrash, and Jewish magical and folkloric texts, it’s just natural to ask if these experiences have been occasioned by the use of psychedelic plants. Phenomenologically, the similarity is obvious.

There are now several articles (and two books) alleging that Jews/Israelites in the time of the Hebrew Bible used psychedelic substances. (There are even more on the New Testament, the Eleusinian mysteries — which, incidentally, is the one argument I do find persuasive — as well as Zoroastrianism, and other ancient traditions.) These include two books by Dan Merkur, The Mystery of Manna (it’s ergot) and The Psychedelic Sacrament; Benny Shanon’s “Biblical entheogens: A speculative hypothesis” (DMT); a really helpful compendium of theories with glosses by Danny Nemu called “Getting High with the Most High: Entheogens in the Old Testament” and an unusual book by psychedelic pioneer Rick Strassman called DMT and the Soul of Prophecy, which proposes that while exogenous psychedelic were not used by Biblical Israelites, much Biblical prophecy might be explained by spontaneous (or divinely-inspired) releases of endogamous DMT in the brain.

Needless to say, I’m not going to review every claim in every one of these sources. But I think it’s worth starting with the negative evidence that few of these authors even mention: there is no mention, or even a hint, of psychoactive sacraments being used in the Biblical period. The sources marshaled by Merkur, Shanon, Nemu, and others are, at best, circumstantial and elliptical. If there had been a psychedelic or shamanic culture in the Ancient Near East, why is it not mentioned anywhere? If these traditions were suppressed, you’d expect them to be banned, like cultic worship of Asherah, sacred prostitution, and other ‘foreign’ worship — or explicitly restricted, if they were only for the elites. But, while there are ample Biblical references to a variety of permitted and forbidden spiritual and even ecstatic practices, there’s no mention of the use of psychoactive substances at all.

Turning to the positive evidence, the claims in these articles and volumes are all extremely speculative. Consider Merkur’s claim about the manna being psychoactive. Biblical texts suggest that the manna was consumed every day. Is this consistent with a shamanic or prophetic use of a psychoactive compound? Daily use? And is it not odd that the theophany at Sinai, the most important visionary experience in Jewish history, took place before this alleged psychedelic ergot was consumed by the Israelites in the desert? Anyway, the majority of Biblical scholars and archeologists doubt that the Exodus ever took place, certainly not as described by the syncretic and self-contradictory texts that were only codified hundreds of years after these alleged events took place. And what about the magical/supernatural properties of manna as described in the Torah, e.g. that it decays every day but not on Shabbat? There’s no textual evidence that manna was meant to refer to a psychoactive substance, rather than a myth about Divine providence and sustenance in the middle of a hostile desert.

Or consider Shanon’s provocative thesis that Biblical Israelites may have blended acacia bark (which contains DMT) with Syrian rue, aka peganum harmala (which contains the MAOI harmaline), to make an ayahuasca-like potion. Yet there is no evidence that these substances were combined, that acacia was used as a sacrament (it was used extensively in sacred architecture, but that is different), or that peganum harmala was even known to Biblical Israelites (it’s never mentioned in the Bible). True, Syrian rue has been widely used in the region for millennia, and, as I alluded to above, has recently been discovered in items used in fertility rites. But it appears to have been used not a psychoactive agent but a medicinal herb.

Nemu makes a somewhat more persuasive case for the incense in the Temple as possessing psychoactive compounds, including possibly cannabis, and there, at least, there is some juxtaposition of the potential psychedelic substance with actual visionary experience, such as the visions of Ezekiel the priest or the early strata of the Hechalot literature centuries later. But even these are, at best, speculations with no direct evidence. The dots are there but the connections are not.

To be honest, I don’t love these last few hundred words of debunking and negativity. Again, I definitely resonate with the desire to find ancient antecedents for a spiritual practice that is so important to so many people today, and in the next section I will attempt to provide some. I don’t want to rain on anyone’s parade, and respect anyone who does find these ancient antecedents inspiring. Anyway, the large majority of religious claims are also probably not historically true, but I don’t go around dumping on them.

I also resonate with the felt sense, in some psychedelic experiences, that this is something ancient and powerful that may indeed underlie the world’s spiritual traditions. There does feel like these practices are core to the human experience generally, and the Jewish experience in particular. Incidentally, that is also true with the Syrian Rue-Acacia brew that some (okay, I) have nicknamed Oyahuasca (“Chaiahuasca” is another version) and which may provide, if not an ancient Jewish medicine, then one which is in a new-old Jewish tradition of sacred plants.

But, look, I’m trained in the academic study of religion, and I question things even when maybe I shouldn’t. I wonder if these efforts to find an ancient usable past are about justifying psychedelic use (a quasi-fundamentalism, really) or about justifying Judaism or the Bible for one reason or another. I wonder if those are desires worth looking at and gently questioning.

In the end, I’m open to being persuaded. I’m an agnostic on this question, not a disbeliever. But not a believer either. I do, however, have an alternative.

3. Grammar, not Vocabulary

While I don’t see evidence for ancient psychedelic use in the Biblical or Talmudic period, I do see evidence for a very similar pattern of spiritual practice.

In other writing on this subject, I’ve described this pattern using the analogy of grammar and vocabulary. We don’t have proof of an ancient psychedelic “vocabulary” – i.e. compounds used to create altered states of mind. But there is abundant proof of an ancient psychedelic grammar of prophetic/ revelatory/ visionary/ spiritual experience: do a mind-altering practice, have some visionary experience, and gain prophecy, healing, or wisdom as a result.

There is tons of that.

Fasting is the most common such practice (see Exodus 34:28, I Samuel 28:20, Daniel 10:2, Judges 20;26, Joel 1:14, Zohar 1:4a-b), and has been used for generations to augment prayer or orient the mind to contemplation; this is true even today. There are references to shamanic and magical practices throughout the Bible, such as the woman of En-Dor raising King Saul from the dead; we don’t know what techniques she used, but that certainly qualifies as a non-ordinary experience that leads to a kind of revelation. While he was alive, Saul was described as being “among the prophets” and engaging in ecstatic dance and, perhaps, speaking in tongues. There are references to (forbidden) sexual cultic ritual, witchcraft, magic, and religious rites. There is the account, which I’ve taught as a kind of manual of meditation, of Elijah’s visions and hearing of the Divine in a “thin, quivering voice.” (‘Still, small voice’ is perhaps a more poetic phrase.)

And in more recent (but still centuries-old) contexts, trance techniques are frequently employed to cultivate non-ordinary minddstates, as discussed in Jonathan Garb’ Shamanic Trance in Modern Kabbalah and Moshe Idel’s work on Abraham Abulafia. Kabbalists cultivated ecstasy in collective textual improvisation, lay on graves to commune with the souls of the departed, spoke with spirit guides (maggidim), engaged in ecstatic unitive prayer, contemplated the heavenly palaces, visualized the chariot of the divine — there is no end to their visionary practices, and throughout, the grammar is consistent: the mind is altered using a practice that enables non-ordinary perception, and some kind of prophecy or revelation is obtained. Sometimes that revelation is simply istkeit, as Huxley wrote: the doors of perception must be cleansed for the isness of reality to be seen. And sometimes these mystics encounter other layers of reality, other entities, even the personified Divine. There is no one mystical or psychedelic or spiritual experience. But there is a basic grammar that unites them.

This vast collection of visionary and mystical phenomena, not whether someone drank or smoked something, comprises the Jewish lineage which contemporary psychonauts have inherited.

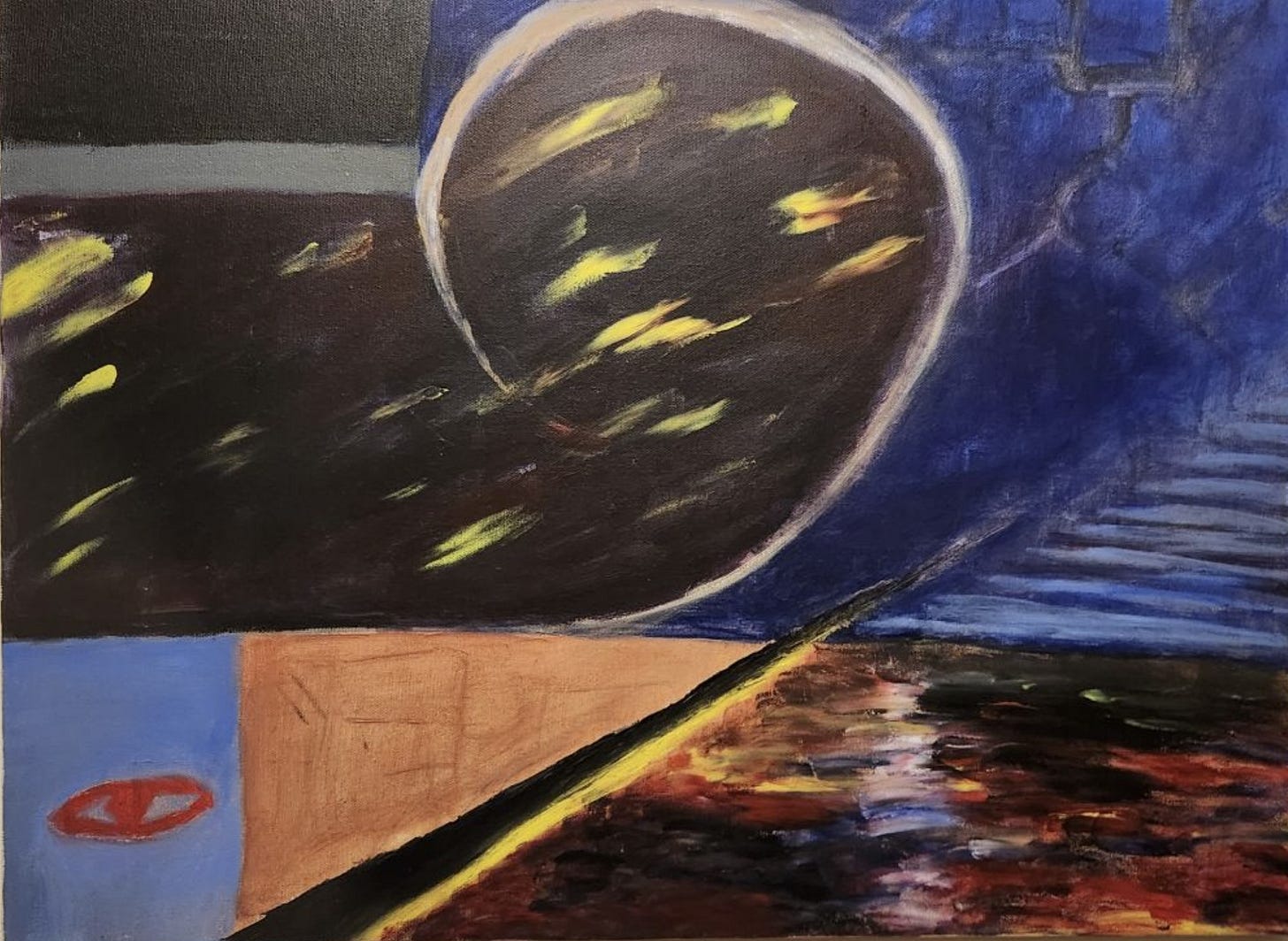

Notice too that it’s the fruits of the experience, not the experience, that are centered in these accounts. Yes, Jewish prophetic experiences, like psychedelic ones, frequently include powerful visions: Israelites on Mount Sinai seeing the “feet” of Yahweh; Ezekiel seeing the Divine Chariot and the bizarre creatures who drive (or constitute) it; Abraham Abulafia’s trance communications with Metatron and very familiar-seeming somatic experiences; Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai or the Ba’al Shem Tov ascending to heaven to meet the Messiah. But in all these (and many more) cases, the bells and whistles of the visionary experience are secondary to the prophecies and insights that it yields.

Consider, once more, the revelation at Sinai. What Moses saw is only barely described in the text, but the minutiae of the Ten Commandments and ensuing tort law is exquisitely detailed. To take another example, Kabbalists and Hasidim meet the Messiah not to bathe in his glory but to ask him when he is coming to alleviate suffering on earth, and to see what they can do to expedite it. Abulafia’s ecstasy was not an end in itself, but a means to attuning to prophecy. Even Ezekiel’s revelation, which is more detailed than others, exists as a prelude to the several chapters of prophecy that follow.

So too, I think, with “prophetic” experiences occasioned by psychedelics. Sure, the fractal imagery of some medicines, the impossibly complex visual experiences of others, and the felt sense of being in the presence of other entities are all remarkable – the latter significantly shook my cosmological/theological suppositions when I first experienced it in 2007. But the fireworks display is of far less enduring value than whatever healing, insight, or communication might take place in such contexts. After all, the experience fades, but the integration of insights that come from it has lasting impacts.

This is also true for what I think is the most common non-recreational form of psychedelic use among Jews, which is less about revelation than healing. As I’ve written about in the last two weeks, psychedelics complicate the distinction between healing and spirituality. In many indigenous cultures that include psychedelics within them, the distinction itself makes no sense. But what I mean here is the use of psychedelics as, paraphrasing a term once applied to Rabbi Isaac Luria, “physicians of the soul.”

Psychedelics tend to bring up one’s “stuff” – trauma, neurotic psychological patterns, ways in which we’re cruel to ourselves and others, family relationships, challenges around sexuality and gender, you name it. And Jews – we have a lot of stuff. Whether you believe ancestral trauma is passed on purely psychologically or whether it is inherited genetically, Jews have a lot of it: centuries of vulnerability and persecution, the Holocaust, Israel/Palestine, contemporary antisemitism. This isn’t the sum total of the Jewish experience, thank heavens, but it is a big part of it, and it often shows up in weird ways: difficulty forming relationships, paranoia, aggressive communication styles, excessive fear and reactivity, distorted ways of seeing oneself (and one’s nation-state), and many others. Nu, what do you expect?

Psychedelics—like therapy, meditation, and many other modalities—can, if used carefully and responsibly, surface traumatic material in ways that are deeply healing. I’ve seen it happen, often with astonishing rapidity and durability. But because of this power, and because of the suggestibility that psychedelics create, a great deal depends upon the ethical commitments of the facilitator. In my twenties, I “surfaced” plenty of difficult stuff without adequate (or any) support, and even “recovered” memories that weren’t actually real. Nor are all pathways of healing equally beneficial; psychedelics’ capacity for suggestibility can also reinforce reactive senses of fragility or peril, leading to an intensification of harmful psychological patterns like nationalism or ethnocentrism or psychedelic messianism. It’s not simple.

My sense of the Jewish sacredness of psychedelics is primarily focused on their capacities for wisdom, healing, and revelation in the present, not the past. But it is in congruence with the ways in which mind-altering practices are described in Biblical, Talmudic, and mystical texts. The technology is, I think, new. But the purposes of the work are ancient.

Gleanings from Visionaries Past

Lastly, when one looks to Jewish visionary texts, rather than evidence of psychedelic use, as our antecedents, we find a trove of ancient wisdom that can inform our practice today, which as I discussed last week, is cause for concern as much as enthusiasm.

For one thing, Jewish tradition and responsible psychedelic practice are also very clear that such journeys are not for everyone, and that they are best taken with preparation, guidance, and integration afterward. The Jewish mystical tradition is full of warnings regarding the mystical path. Probably the most famous is the tale of the four Talmudic rabbis who entered Pardes – paradise. Of the four, only Rabbi Akiva returned as he was. One died, one went mad, and one (Aher) became an apostate. (I’m not sure Aher’s was a negative outcome, but that’s a different article.) Those aren’t good odds, especially for unprepared day trippers. So too the warnings against practicing Kabbalah without the ballast of years, training, and community – boundaries set after the messianic heresies of Sabbetai Zevi and Jacob Frank.

Mysticism and prophecy – whether created by trance practices, fasting, psychedelic medicines, or other forms – can be enormously powerful. They can also destroy a person if there is no preparation, container, guide, community, or integration.

In addition, as I’ve already mentioned, the Jewish prophetic experience is one of oscillation between individual and community. With the exception of the revelation at Sinai, these experiences take place alone or in very small groups. Yet communal forms and norms shape both the contours of prophetic experiences and the integration of them into ethical and ritual life. We bring our hopes, baggage, concepts, assumptions, and theologies with us, even if the peak of the psychedelic experience seems to transcend all of them.

The Ba’al Shem Tov practices a mystical ascent, perhaps drawing on Sufi as well as Jewish techniques of ecstasy, and his experience is thoroughly infused with Yiddishkeit. (Consciously building on that model, Rabbi Zalman Schachter Shalomi wrote about his experiences in the same terms, as an “ascent of the soul.”) We ascend the sacred mountain, but eventually return to the camp below, in a cycle of society and solitude.

What does it mean that these principles derived from the literature of Jewish spiritual experience are applicable to psychedelic spiritual experience as well? I think it points to a continuity of spiritual practice, despite the novelty (for Jews) of the means of ascent. We are doing similar things here, we mystics from across the ages, even as so much is different today. We are living in the alt-neu, the old-new — which is, perhaps, where we Jews have always made our homes.

I have to say, I am really enjoying putting this psychedelic series together for you. Thanks for reading. Most of my time over these last few weeks has been spent on this subject: on projects at Emory and Harvard, and writing these articles.

I’ll be co-leading a five-day silent meditation retreat combining insight meditation and Jewish practice, from December 23-27 in Connecticut. Here’s the info.

Also in the contemplative realm,

just wrote yet another excellent piece on what deep contemplative practice is really like. I think Sasha has now done the best writing on this subject of anyone I’ve read.Here’s some political stuff I’ve benefited from reading on Substack lately:

- published a great quote from transgender member of congress Sarah McBride, who has been treated awfully and responded with dignity and intelligence.

And on the Bad Guy Beat,

did great coverage of the GOP’s plans (real, now that the election is over) to gut social security; did a fantastic piece on Pete Hegseth and masculinity; and did an excellent deep dive into the continued enshittification of X.